If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to begin this post with a cheap trick: how many of you marketers, advertisers, researchers, corporate strategists and consultants out there have been asked to “find out what’s important to [some audience]?” While I don’t actually expect any of you are sitting there with a hand raised in the air (kudos if you are, though), I’m betting you’re probably at least nodding to yourself. Whatever you’re selling, the basic steps to market a product are simple: figure out who wants it, what’s important to them, and how to communicate that your product delivers on whatever they find to be important to encourage some behavior. No one ever said marketing was rocket science.

But no one ever said it was easy, either. And determining what’s actually important to your customer isn’t merely another task to check off, it’s a critical component on which a misstep could derail years of effort and potentially billions in R&D spending. I always tell my clients that you can design an absolutely perfect product, a masterpiece of form and function, but if you can’t communicate why it’s important to someone, there’s no reason for anyone to buy it. As my esteemed colleague Andrew Wilson will tell you, not even sliced bread sold itself.

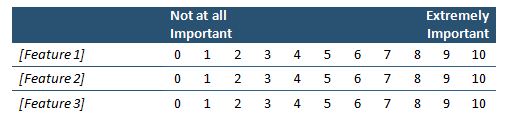

So that brings us back to that original, fundamental question: how do we “find out what’s important?” The simplest method, of course, is simply to ask. If you’ve ever looked at a research questionnaire, chances are you’ve seen something like this:

When considering purchasing [X/Y/Z Product] from [A/B/C Company], how important to you is each of the following?

This concept, generally known as Stated Importance, is one of the oldest and most used techniques in all of marketing research. It’s easy to understand and evaluate, allows for a massive number of features to be evaluated (I’ve seen as many as 150), and the reporting is quick. It produces a ranked list of all features, from 1 to X, giving seemingly clear guidelines on where to focus marketing efforts. Right?

Well, now hold on. Imagine you have a list of 40 features. What incentive is there to say something isn’t important? Perhaps “Information Security” is a 10, whereas “Price” is a 9. But if everyone evaluated the list that way, you’d find that almost all of the features were “important.” In fact, I’ve found this to be common across industries, products, audiences – you name it. While you can still rank them 1 – 40, there’s little differentiation between the features, and you’ve just spent a big chunk of research money with little to show for it.

By the way, these two features (“Information Security” and “Price”) are, in my experience, two aspects that almost every research study includes, and which virtually always come up as being highly important. So, using a stated measure only, one might conclude that the best features to communicate to your customers are security and costs.

Now, let’s consider the other general way of measuring importance: Derived Importance. There are many methods to measure derived importance, but they all involve one general rule: they look for a statistical relationship between a metric, like stated importance, and a behavior – common ones include likelihood to purchase or brand advocacy. You might use the same question as above, but instead of using a 1 – 40 ranking based on what consumers say, you could instead look for a relationship between what they say is important and their likelihood to purchase your product.

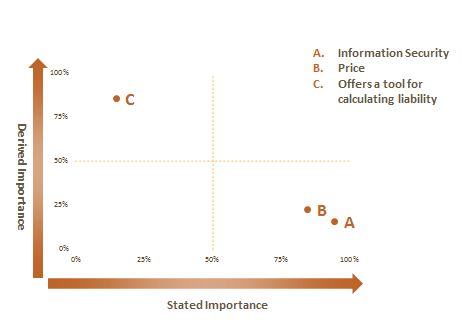

That brings us back to the question of “account security” and “price.” We know from our discussion of stated importance that most consumers will score these very highly. But check out what tends to happen when we look at derived importance (using an example from an auto insurance company):

The chart above is something every marketer and advertiser on the planet has probably seen 1,000 times, so bear with me. On the vertical, or y-axis, we have our derived importance score, the statistical relationship between importance and likelihood to purchase, advocate, or whatever other behavior might be appropriate depending on where you are in your marketing funnel. On the horizontal, or x-axis, I’m showing stated importance, or how important consumers said these features were when purchasing from Auto Insurance Company X (all of these numbers are made up, but you get the idea).

You’ll see that, as expected, information security and price perform very well on the stated measure, but low on the derived measure. What we can infer, then, is that while most of the consumers interviewed in this made-up study say information security and price are very important, these features don’t have a strong relationship to the behavior we want to encourage. These are commonly known as table stakes, or features that everyone says are important but don’t really connect to purchase, advocacy, and the like.

But since the third feature, offering a tool for calculating liability, has a much stronger relationship to our behavioral measure, what we can infer is that while fewer consumers said this was important, those that did view it as important are the most likely to purchase from or advocate for Auto Insurance Company X. So if you had to pick one of these three features on which to hang your marketer’s hat, we’d recommend the tool for calculating liability – since it’s our job as marketers to figure out what’s going to encourage the behaviors we want, and then communicate that to our customers.

I hope this discussion has lent you some knowledge you can pass along to your clients, internal partners, fellow consultants, friends and whomever else. There are many ways to calculate derived importance, and many clever techniques that improve on traditional stated importance (like Maximum-Difference Scaling or Point Allocations). But if you take one thing from this post, let it be this – in this crazy, tech-driven world we live in, simply asking what’s important just isn’t enough anymore.

Nick is a Project Manager with CMB’s Financial Services, Insurance & Healthcare Practice. He enjoys candlelit dinners, long walks on the beach, and averaging-over-orderings regression.

Speaking of romance, have you seen our latest case study on how we help Match.com use brand health tracking to understand current and potential member needs and connect them with the emotion core of the leading brand?