Did I snag you with the title? I hope so—it took me quite a while to come up with it. As our regular readers and esteemed clients know, each of CMB’s employees contribute to our blog by writing at least once annually. In the past, I’ve used my posts to tackle the real-world applications of complex mathematical topics, including statistical significance, Maximum-Difference scaling, and stated vs. derived importance.Today, though, I’d like to introduce you to my true research passion: brand positioning. My first job in the research field took me all over the world as my team and I worked to determine and deliver the most effective positioning for a multinational insurance company. I’ve been hooked ever since.

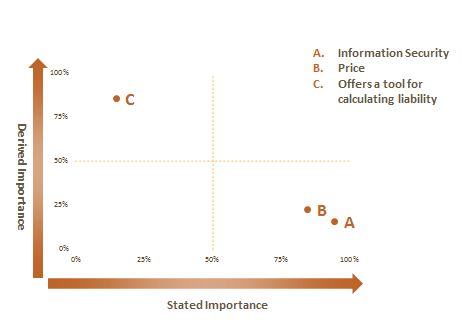

Did I snag you with the title? I hope so—it took me quite a while to come up with it. As our regular readers and esteemed clients know, each of CMB’s employees contribute to our blog by writing at least once annually. In the past, I’ve used my posts to tackle the real-world applications of complex mathematical topics, including statistical significance, Maximum-Difference scaling, and stated vs. derived importance.Today, though, I’d like to introduce you to my true research passion: brand positioning. My first job in the research field took me all over the world as my team and I worked to determine and deliver the most effective positioning for a multinational insurance company. I’ve been hooked ever since.

Most of you reading this have probably heard the term “positioning” before, but for those who haven’t, here’s a definition from the guys who (quite literally) invented the field: “An organized system for finding a window in the mind. It is based on the concept that communication can only take place at the right time and under the right circumstances.” - Ries, A. and Trout, J. (1977), Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind.

A simpler definition, also from Jack Trout, would be this: “the place a product, brand, or group of products occupies in consumers' minds, relative to competing offerings.” Pretty simple, right? You define your brand as the collection of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors you want your consumers (whomever they may be) to have about you, relative to your key competitors (perhaps the most famous “opposition branding” of this sort is 7 Up’s classic “The Uncola”).

So, we need to identify the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors we want consumers to have and then make a big, direct marketing push to communicate those aspects to them. Right? (Obviously, there’s a lot more to it than that.) In a future blog post, I’ll tackle aspects like value statements, foundational benefits, key goals, and the like, but for now, I want to focus on one major sticking point I keep seeing come up: emotion.

These days, marketers talk endlessly about “big data” and “connecting on an emotional level.” How can we convince so-and-so to love our brand? What emotions do we want associated with our brand? Are we happy? Exciting? Stoic?

Research firms, including ours, often tackle these questions and try to help clients be seen for the right emotions. But here’s the rub: unless your product or company is brand-spankin’-new, the basic emotional reactions to your brand are already defined. Try as we might, changing an idea in someone’s mind is by far the most difficult task in all of marketing, and if people in a focus group are saying your brand reminds them of a Volvo, the odds that you can convince them to think of your brand as a Ferrari are virtually nil.

So how can brands connect with consumers on an emotional level, convey the right emotions, and do so effectively in an already over-communicated world? Well, that answer would be too long for this blog post, but let me start with a simple analogy: brand positionings can be thought of as a ladder—you have to climb one rung before you can move on to the next. The very bottom is your foundation (what industry you’re in, when you were founded, etc.– just the facts, Jack), and the very top is your emotional connection to your consumers, inasmuch as one exists. In between is an array of needs, including functional benefits, the value statement, goals, and a few others I’ll cover in a future blog.

Brands have to build up to that emotional connection, which is usually the most difficult component of branding (and why it’s at the top of the ladder). Brands or products can do so by delivering across the entire spectrum in a consistent, thorough way that speaks to the emotion you want to own. If you have major delivery issues, you won’t be thought of as reliable. If you’ve only existed for 2 months, you probably can’t own trustworthy. Oil companies can’t be fun. If you want to own reliability, you need top-level customer delivery, including responsive employees, a reputation for customer service, and a culture that rewards proactivity. You get the idea.

By now, you’re probably wondering what this has to do with my new Prius (good timing!). Outdoorsy, environmentally-friendly folk like myself have been long-devoted fans of Toyota’s original hybrid fuel cell vehicle for its emissions-slashing, fuel-saving engine among other things. But those aren’t emotions, and no one could think the Prius’ historical sales records could be accomplished without more than a dash of emotional connection thrown in.

So how does the Prius make me feel? Like I’m making a difference. The “hybrid” stamp on the back reminds me not to be wasteful. The constantly-cycling energy meter not only encourages me to drive less aggressively, but also turns reducing emissions into a fun little game I play driving around Boston. (54 mpg? Psssh. I can do better.) A solar-powered climate roof reminds me not to waste energy and makes me smile when it unexpectedly turns on. A cynic might say that what the Prius really does is allow people to feel better about themselves, and I don’t deny there’s at least a kernel of truth there, too.

You can see how the positioning of the Prius fits the ladder example: the foundation is the hybrid engine, 14 years of existence, and Toyota brand. Functional benefits include cutting gas costs and reducing emissions (the proof points are well-known) while supporting the goal of living a low-emission life. All of these things add up to that simple, good feeling I have whenever I slide behind the wheel, which connects me with the product in a way that the individual features cannot. The cycling energy monitor is cool, but I wouldn’t have assigned point values for efficiently driving away from stoplights around my neighborhood if it was just a toy. The solar roof not only helps keep the car cool in the summer, it reminds me to be energy-conscious at home, too. Seamless alignment between functional and emotional.

Let this be the first lesson then: brands can own emotions, but not without much effort. If you want someone to love your brand, you have to give them reasons why they should, and all of those reasons need to work in tandem with one another to create a whole greater than the sum of its parts. In a future post, I’ll show you how.

Nick Pangallo is the Senior Project Manager on CMB’s Financial Services, Insurance, Travel, and Hospitality team. He’s an avid poker player and an occasional lecturer at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management. You can follow him on Twitter @NAPangallo, though be warned: he often tweets about the Buffalo Bills.

A few weeks ago, I found myself seated at a trendy Mexican restaurant in Minneapolis, an eager participant at one of the more enjoyable business lunches I’ve encountered lately. As you might expect, the topic quickly turned from the vagaries of the marketing life to the weather, summer vacation stories, the gym, far-too-early holiday planning (I’m looking at you, Target), and then, unexpectedly, to dieting. It was there where I learned

A few weeks ago, I found myself seated at a trendy Mexican restaurant in Minneapolis, an eager participant at one of the more enjoyable business lunches I’ve encountered lately. As you might expect, the topic quickly turned from the vagaries of the marketing life to the weather, summer vacation stories, the gym, far-too-early holiday planning (I’m looking at you, Target), and then, unexpectedly, to dieting. It was there where I learned