Late last month, the Boston Celtics were struggling along in the middle of the NBA standings. They weren’t great and they weren’t awful, but they were predictable—predictably middle of the pack. But star point guard Rajon Rondo was having another terrific year, racking up triple-doubles (achieving double digits in scoring, rebounds and assists) at twice the rate of his closest rivals. He was the Celtics top performer and the key to what limited success they were having. So when Rondo went down with a season ending knee injury on January 25th die-hard Celtics fans went from disappointment to outright depression.Then something surprising happened.

Late last month, the Boston Celtics were struggling along in the middle of the NBA standings. They weren’t great and they weren’t awful, but they were predictable—predictably middle of the pack. But star point guard Rajon Rondo was having another terrific year, racking up triple-doubles (achieving double digits in scoring, rebounds and assists) at twice the rate of his closest rivals. He was the Celtics top performer and the key to what limited success they were having. So when Rondo went down with a season ending knee injury on January 25th die-hard Celtics fans went from disappointment to outright depression.Then something surprising happened.

Prior to Rondo’s injury the Celtics had looked tired; they suffered from low energy and lack of enthusiasm for moving beyond their very ordinary performance. After the injury they looked like a bunch of kids bursting through the door on the last day of school. What happened? They were playing the same game, but had changed (out of necessity) the way they were playing it. Skills that had been lying dormant suddenly came to the fore. They were energized, they were playing much better defense and they were moving the ball much more effectively on the offensive end of the floor. The Celtics went on a tear, winning 8 out of 9 games over the next 3 weeks, and potentially changing the entire trajectory of their season.

So what does this have to do with research? Maybe a lot. Ongoing tracking programs like customer experience and brand health tracking are especially susceptible to becoming “tired” – continuously delivering the same things over and over, with diminishing returns. One of the biggest challenges facing Celtics Coach Doc Rivers was figuring out how to pull his team out of the middling rut they’d gotten comfortable in. In his case, the team was forced to change due to their star player’s injury. Fortunately, customer insights folks don’t need such a dramatic trigger.

Here are three things you can do to breathe new life into tired tracking programs, and “up your game”:

Introduce “Deep Dives” Incorporating “deep dives” into your program is a great way to get more and more useful insights into critical issues, without the time and cost of a separate project. A few examples of potential deep dive topics:

- Product enhancements

- Customer decision drivers

- Competitive comparisons

- Internal performance comparisons

Integrate your tracking data with data from other sources: Tracking measurement alone (no matter how well designed) isn’t capable of informing all of the insights your internal clients need. “Connecting the dots” between the measurement and other business data can help you deliver new, more useful insights. I’m not talking about a “millions of dollars and thousands of lives” IT initiative here. You’ll be surprised how much useful insight you can get by focusing on a specific business issue with data sets that you can readily get your hands on.

Put insights directly into users’ hands in a way that helps them act: If your internal customers are using dashboards or portals to view tracking results, do those tools really help them take action, or are they really just data dashboards. A dashboard needs to tell the end-user 4 things, customized to their roles and responsibilities: they need to know where they stand; what will have the highest impact on key business goals; they also need the need the tools to prioritize and plan actions, and show whether the actions taken are really working.

Put insights directly into users’ hands in a way that helps them act: If your internal customers are using dashboards or portals to view tracking results, do those tools really help them take action, or are they really just data dashboards. A dashboard needs to tell the end-user 4 things, customized to their roles and responsibilities: they need to know where they stand; what will have the highest impact on key business goals; they also need the need the tools to prioritize and plan actions, and show whether the actions taken are really working.

So, has your customer experience or brand health tracking program grown “tired?” If so, what will you do to up your “game?”

T.J. is CMB's Chief Strategy Officer and General Manager of our Tech Solutions Team. His twin boys are enjoying a re-energized Celtics above.

Here’s an example from another industry: homebuilding. I’ve seen surveys that ask buyers to rate the window quality in the home. Why?!? Shouldn’t the builder know if the windows they are putting into the home are high-grade or low-grade? Remember, we’re assessing the home purchase experience, NOT homebuyer preferences. If you’re trying to achieve both in the same research study, you’re going to be (as Mr. Miyagi says) “like the grasshopper in the middle of the road.”

Here’s an example from another industry: homebuilding. I’ve seen surveys that ask buyers to rate the window quality in the home. Why?!? Shouldn’t the builder know if the windows they are putting into the home are high-grade or low-grade? Remember, we’re assessing the home purchase experience, NOT homebuyer preferences. If you’re trying to achieve both in the same research study, you’re going to be (as Mr. Miyagi says) “like the grasshopper in the middle of the road.”

4. Pay attention to word of mouth and the lifetime value of customers.

4. Pay attention to word of mouth and the lifetime value of customers.

Naturally, by basing decisions unquestioningly on what consumers asked for, Komar and Melamid came up with a beauty. It’s a perfect combination of a pleasant blue sky, scenic mountains, frolicking deer, a picnicking family, and George Washington pondering life smack dab in the middle. It is a scene that has everything, and it's brilliant social commentary—but J.M.W. Turner it’s not.

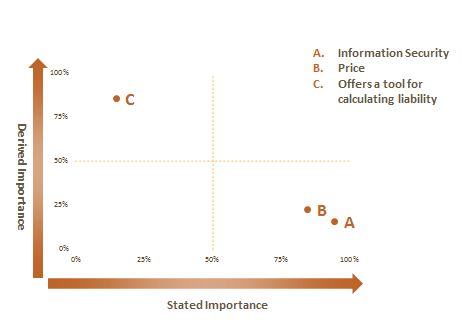

Naturally, by basing decisions unquestioningly on what consumers asked for, Komar and Melamid came up with a beauty. It’s a perfect combination of a pleasant blue sky, scenic mountains, frolicking deer, a picnicking family, and George Washington pondering life smack dab in the middle. It is a scene that has everything, and it's brilliant social commentary—but J.M.W. Turner it’s not. But above all the biggest takeaway for me, from “The Most Wanted” painting, is that thoughtful actionable research starts with the end in mind. We researchers can’t measure needs, wants, and preferences for specific elements in the design without any forethought about the final results of the potential outcomes.

But above all the biggest takeaway for me, from “The Most Wanted” painting, is that thoughtful actionable research starts with the end in mind. We researchers can’t measure needs, wants, and preferences for specific elements in the design without any forethought about the final results of the potential outcomes.